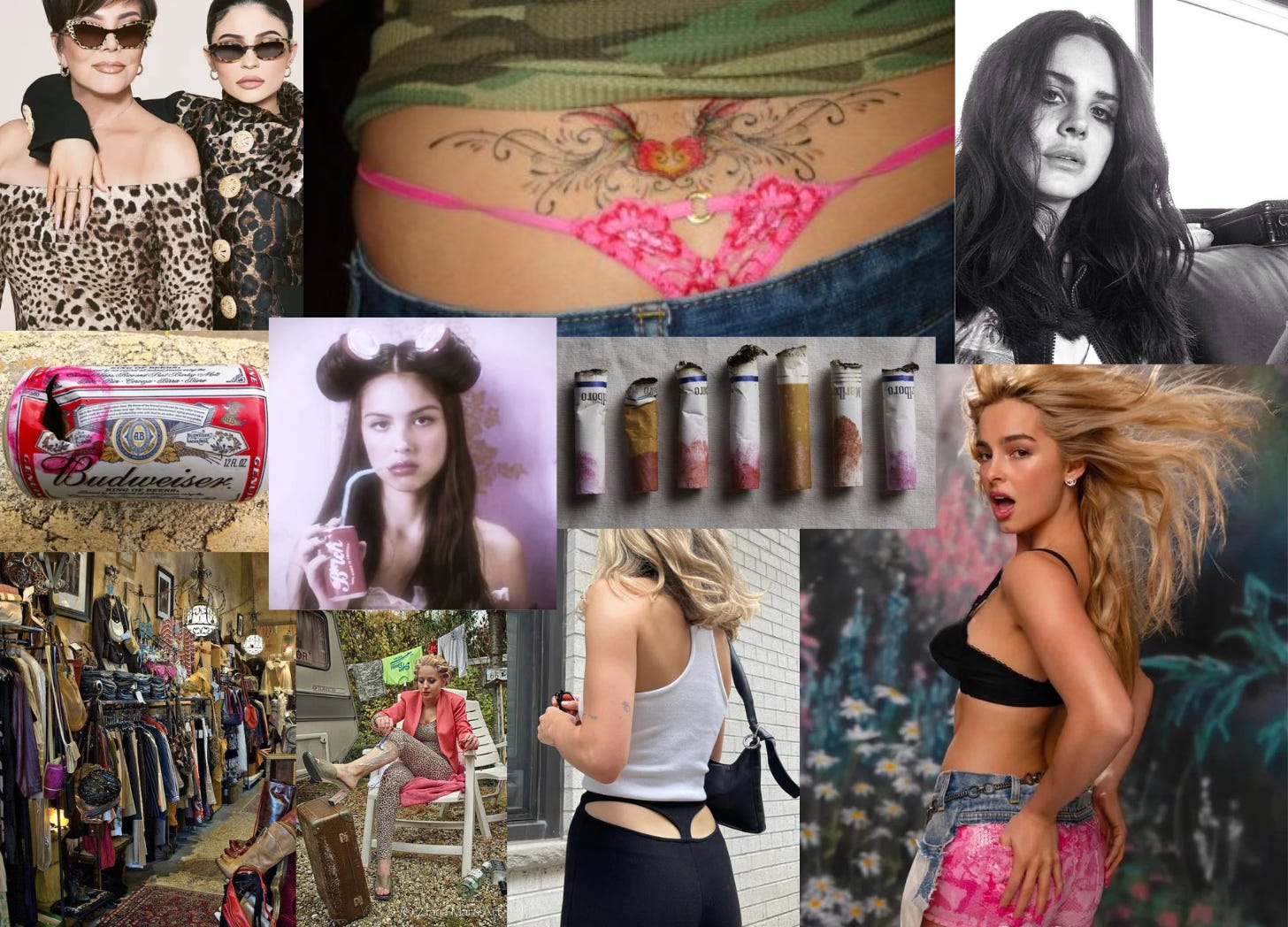

Picture this: a pop star in $3,000 Balenciaga sweats, smudged eyeliner, and a Marlboro Light dangling from manicured fingers. She’s not on her smoke break from a minimum-wage job—she’s on the cover of Vogue. Her hair is intentionally greasy, her thong is intentionally visible, and her wardrobe costs more than your rent. She’s not struggling—she’s styling. The “white trash” aesthetic isn’t dead; it’s had a spa day and come back ironized, filtered, and sold on Depop for $80.

We’re living in a moment where looking broke is trending, but being broke is still criminalized. The “white trash” aesthetic—once a classist slur, now a curated vibe—has become cultural currency. It’s the new camp. The twist? It’s only “cool” when worn by people who’ve never been truly close to desperation.

Poverty, But Make It Pretty

This isn’t new. Fashion has long borrowed from working-class aesthetics: denim was once utilitarian, flannel was for lumberjacks, and sneakers were for laborers. But the 2020s have taken the trend from subtle inspiration to full-on cosplay. Call it “recession core,” “cigarette mom,” or “hot mess chic”—whatever you name it, it’s performance poverty for people who can afford to leave it behind.

We’re seeing a boom in nostalgic grime: DIY baby tees, busted Converse, and gas station glam. There’s something particularly jarring about watching influencers sip canned beer by a dumpster “for the aesthetic,” only to hop into a Mercedes after the shoot.

And yes, we’re in a recession-adjacent moment. Groceries cost more, wages haven’t kept up, and young people are increasingly squeezed out of housing and healthcare. But instead of facing that reality, we’re aestheticizing it. Fashion becomes a coping mechanism: if you can’t beat poverty, make it a look.

The Rise of the Cigarette Mom and $90 Thrift Tees

Nothing screams “we’ve hit a cultural wall” like watching rich girls emulate the ‘90s mom who microwaved taquitos and smoked indoors.

The “cigarette mom” aesthetic is all over TikTok. Think: frosted lips, ashtray eyeliner, messy buns, and a vaguely chaotic energy that signals she’s lived. But she hasn’t. She’s just watched Euphoria. It’s not the trauma—it’s the vibe. What once signified hardship and dysfunction is now curated into a cute Instagram photo dump.

And then there’s the thrift economy. Thrifting used to be for the broke and resourceful. Now? It’s curated, upcycled, and absurdly overpriced. Vintage shops in gentrified neighborhoods are slinging old Hanes tank tops for $45 and calling it “y2k streetwear.” On Depop, teens are selling 2007 Kohl’s blouses for the price of a new iPhone case.

All of this points to one thing: the things poor people wear out of necessity are being rebranded as aspirational by those who never had to make do.

Pop Stars and the Poverty Cosplay Parade

Let’s talk about our aesthetic leaders.

Lana Del Rey practically invented glamorous destitution. Her songs drip with sad Americana, her visuals recall roadside motels, bruised knees, and the scent of Pabst Blue Ribbon. It’s beautiful. But it’s also make-believe.

Kesha’s early days were glitter-trash glory: brushing teeth with Jack Daniels, dirty sneakers, party girl despair. But it was fun because we knew it was a character.

Olivia Rodrigo, Charli XCX, and even Doja Cat have all dabbled in looks that once meant “unstable upbringing,” now sold as “high fashion mess.”

The aesthetic cues are deliberate: chipped nails, visible roots, fast food as a prop. But their version of "white trash" is polished just enough to be palatable. They get to wear it like a mood board. Real people don’t.

When Camp Is Just Camouflage for Privilege

To be clear: aesthetics are not inherently evil. Personal expression, nostalgia, and subversion have their place. Camp—true camp—is often rooted in reinterpreting power, turning pain into art. But this? This feels less like art and more like irony wrapped in apathy.

There’s a difference between critiquing class structures and making them cute. You can’t romanticize the symbols of struggle without acknowledging the systems that created them. You can’t wear the uniform of poverty and walk away from the consequences.

It begs the question: who gets to look poor and be celebrated for it? Who gets left with the real thing?

Because for a lot of people, white tank tops and ratty jeans aren’t a vibe. They’re all they have. And that difference? That’s not camp. That’s class.

TL,DR

The Campification of White Trash isn’t just a trend. It’s a recession-era mirror. We’re glamorizing what people are actively trying to escape from. It’s not about shame—it’s about awareness. About asking why we find poverty palatable only when it’s posed and pretty.

So next time you see a $600 “vintage” hoodie or a pop star dressed like she’s late to her diner shift, ask yourself: who’s really in costume?

i like the way you write

Amazing piece!